“My father, Con Kelly, was a farmer whom I remember with great fondness as a hardworking, good-humoured man. He died at the age of 93 in 1979. Unfortunately, I was confined to bed with flu on the small island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean and was thus unable to make it home. A telegram brought the sad news, and I shed silent tears thousands of miles away.

He was known in the neighbourhood of Ballinvalley and Gurteen as a community-minded man. On one corner of his farm, he donated the site for Gurteen hall, the ivy-clad remains of which still survive just a stone’s throw from Gurteen bridge.

On the same field never tilled, hurling matches were played between Killeigh and Killurin schools during the hard lean times of the Second World War. Only one ‘sliothar’ was minded carefully between contests as a treasured, irreplaceable possession.

On the same ground, he gave weekly access to the training of young men in the Local Security Force, Ireland’s own Dad’s Army, later to become the Local Defence Force and the FCA. Once a week, officers from the Curragh arrived to put the local lads through their paces, drilling, marching and handling various weapons. My brother Tom and I, both pre-teens, attended most of these sessions and were greatly entertained in an age when there was little else by way of novelty to pass the time.

We did our drilling and marching at home. We could respond to all military commands, attach a bayonet to a rifle and lob a hand grenade with reasonable accuracy, our ‘arms’ wholly homemade. The trainees were supplied with full uniforms made from a coarse material sometimes referred to as “bull’s wool”. In addition, strong brown boots, a warm greatcoat, leggings, and a cape were prized when clothing ration was the order of the day in civilian life. It was not uncommon to see a man heading to work on a cold day in full military gear.

It would be very hard for a person in the area in the 21st century to visualise the place that Gurteen Hall held in the social life of the 1940s. The conflict in Britain led to many small travelling dramas and entertainment groups moving between venues in neutral Ireland. Gurteen Hall saw many of these groups perform, and my brother Tom and I were thrilled to be part of all this.

Though now in my eighties, I can still vividly recall plays and songs that I first enjoyed from the tiny stage in the Hall in an era when entertainment could only be accessed on foot or by bicycle. There was one English fellow named Jimmy Stone who persuaded Tom and me to supply oats for his horses for the privilege of free entry to the show. We had to ‘steal’ the oats from the loft without letting daddy know.

I am still in awe of those show people who travelled in horse-drawn caravans slowly through the country and set up their dramas and shows in such rudimentary locations. They carried a piano and other stage equipment but often had to supplement their stage supplies such as chairs from us or the Cooks, our neighbours. That they could survive on the meagre takings at the door, their only earnings showed great dedication to their love of performance. The Hall had no electricity or running water. The horses were let loose on the field, and the caravans parked there too. The stage was tiny, and entry to it was directly from the field through a door – no waiting in the wings!

The Hall is so obscured today from the road that most passers-by would be unaware of its existence, but in my youth, it was the social centre of life in our area. On Sunday nights in summer and autumn, there was a whist drive followed by a dance. The light was supplied by Tilley lamps operated by gas and had a delicate burning “mantle” that disintegrated if touched. After the card game, the dance commenced. The ladies lined up on one side and the men on the opposite. Music was supplied by two stalwart accordionists, Frank Dunne and Jim Coonan. Waltzes, quick steps and a variety of Irish dances kept the dancers happy, and no one in those days went to dances without a basic level of skill in these steps.

This insignificant little building, with a corrugated iron roof and never locked day or night, was the unlikely origin of many local romances and marriages. I do not doubt that many passers-by have had fond recollections of the first exciting memories of love in the Hall over the years.

Gurteen bridge was also a social gathering place for young men in those far-off days. They played pitch and toss and chatted for hours, especially on Sundays. Sometimes in summer, they were allowed to stand outside Mrs Carolan’s house, and she would open the window to let them hear Micheál O’Hehir’s commentary on a Sunday Gaelic match. I remember one young emigrant who turned up to the bridge, home from England, in full RAF uniform. One of the young chaps resented his unpatriotic attire and tossed his RAF cap into the river.

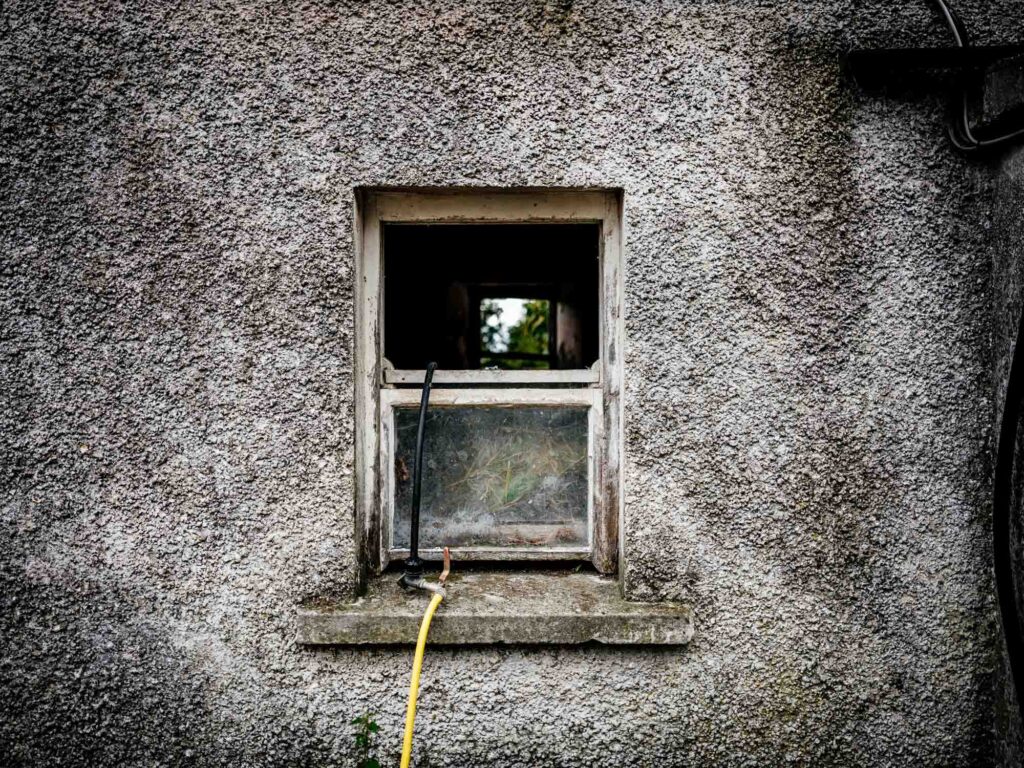

In 1945, aged 13, I left home, the field and the Hall behind. On September 10th of that year, the day I was leaving, men were digging at the back of the Hall, and I was told they were building an “extension”. While I was away, entertainment centres changed in the ensuing years, and over the years, the building fell into decay. The “extension” was a tiny room for boiling kettles, I expect. Today the Hall is an empty, overgrown shell, but when I see it, memories of former wartime “better days” come to mind.

Lately, I have had the opportunity to go around behind the Hall and peer in the glassless windows. The dancing floor is long gone, and graffiti adorn the walls. But the trees and the nearby river are still there. So too are fond memories of fun-filled days of youth which will stay with me to the end of my days”.